The second is defined as 9,192,631,770 vibrations of a cesium atom and measured in a device known as a fountain clock. These work by cooling a tiny cloud of cesium atoms to a temperature close to zero, tossing it up in the air and zapping it with microwaves as it falls.

Then you watch the cloud to see if it fluoresces. This fluorescence is maximised when the microwave frequency matches a hyperfine transition between two electronic states in the atoms, at exactly 9,192,631,770 Hz.

Various labs around the world use this method to run clocks with an accuracy of around 0.1 nanoseconds per day. That’s impressive but not perfect. Fountain clocks have one drawback: the clouds of cesium tend to disperse quickly and that limits how accurately you can take data.

Now there’s a new kid on the block which looks as if it’s going to be better at keeping time.

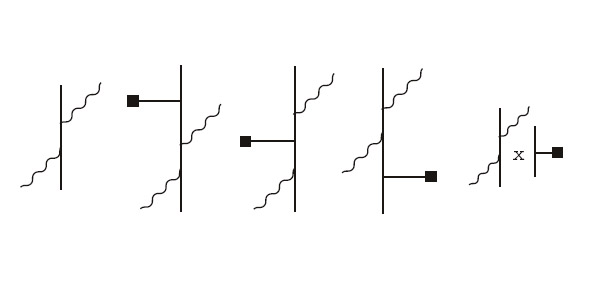

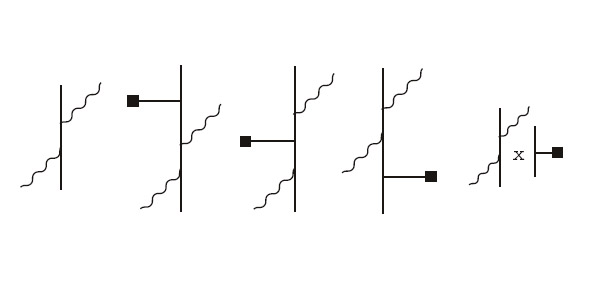

Today some chaps from the the University of Nevada in Reno and the University of New South Wales in Sydney outline a new clock that relies on an effect called the Stark shift in which a spectral line is split by an electric field (this is the electric analogue of the Zeeman effect in which spectral lines are split with a magnetic field).

This is a complex phenomenon but the key thing is that the same electric field can influence the split in different ways. In fact, a couple of groups have recently discovered that in certain circumstances these can cancel out each other at specific “magic” frequencies of an electric field. When that happens, the line splitting vanishes.

This should be pretty straightforward to measure. The electric field is supplied by trapping the atoms in a standing electromagnetic wave, otherwise known as a standard optical lattice. Then change the laser frequency while looking at the atomic spectra. When the line splitting vanishes, you’ve hit the magic frequency.

The big advantage of this method is that you can trap millions of atoms easily in an optical lattice and that should make such a clock much more robust than a fountain, while achieving at least the same kind of accuracy.

So what kind of atom should we choose to sit at the heart of these “micromagic clocks”? The Ozzie-American group says that, contrary to previous reports, cesium does not have a magic frequency and so can’t be used in this technique. Aluminum, on the other hand, should be perfect.

The second is dead, long live the second.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/0808.2821: Micromagic Clock: Microwave Clock Based on Atoms in an Engineered Optical Lattice